This week, prnewswire.com reported on the curious case of Dr. Theresa Cameron, a tenured professor on the faculty at Arizona State. Dr. Cameron, the first African American awarded tenure in ASU’s College of Design, has filed a civil rights lawsuit against the Arizona Board of Regents, ASU President Michael Crow and other ASU officials in response to the University’s decision to terminate her appointment. The prnewswire report summarizes her case:

PHOENIX, Aug. 13 /PRNewswire/ — Dr. Theresa Cameron filed suit today in the U.S. District Court in Phoenix seeking an injunction and other relief against the Arizona Board of Regents; Arizona State University, President Michael Crow; departing Dean of the ASU College of Design, Wellington “Duke” Reiter; Associate Dean Kenneth Brooks; and the former director of the College’s School of Planning, Hemalata Dandekar, alleging violations of federal civil rights and employment laws that make it unlawful to discriminate on the basis of disability, gender or race. Dr. Cameron was the first African-American woman to be awarded tenure in the College of Design when she achieved that accomplishment in 2000. After spending her entire childhood in foster care, Dr. Cameron put her self through college and eventually obtained her Ph.D. in Design from Harvard University in 1991. Her childhood experience is chronicled in her book Foster Care Odyssey in America: A Black Girl’s Story published in 2002. Dr. Cameron and her book were featured in the Arizona Republic in June 2002.

The lawsuit alleges that Dr. Cameron requested adjustments in her teaching schedule and course load beginning in March 2005 when she prepared to return from an approved medical leave of absence and has renewed these requests, all of which were denied, at the beginning of each academic semester. The lawsuit also alleges that at or around the same time, she challenged Dean Reiter on issues relating to pay disparity in the College of Design and offered an affidavit in support of a colleague who had filed suit against the Arizona Board of Regents and ASU President Crow in another federal civil rights lawsuit in Phoenix. The lawsuit further alleges that as a result, Crow, Reiter, Brooks and Dandekar worked together to revoke Dr. Cameron’s tenure and terminate her employment.

While reading of Dr. Cameron’s lawsuit, I was reminded of the precarious position of African American academics — even prominent tenured professors with national and international reputations. I do not know the details of Dr. Cameron’s case, and I am sure that ASU officials believe that they are in the right in terminating her tenure at their institution. Still, the fact that I can easily count of the names of four highly accomplished and prominent Black scholars who have been fired from faculty posts, despite having tenure, concerns me greatly.

Consider the following well-known Black scholars and writers, each of whom was released from a tenured position:

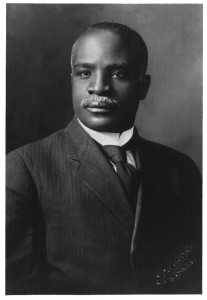

Derrick Bell

Derrick Bell, the Harvard Law School professor who took an unpaid leave of absence two years ago to protest the school’s failure to hire, in his words, “a woman of color,” received notice today that his teaching days there are over because of the university’s two-year limit on leaves of absence.

In a letter from Robert C. Clark, the law school dean, Mr. Bell was told that his refusal to return to the school would be considered a resignation, effective July 1.

Mr. Bell, Harvard’s first black tenured law professor, had asked the law school in February to extend his leave of absence, on the grounds that he left for “reasons of conscience.”

Although Mr. Clark said he was “saddened” by Mr. Bell’s decision not to return to the school, he wrote, “I continue to believe that the path of protest you have chosen — withdrawal from the law school community — is an unfortunate one.” —New York Times, July 1, 1992

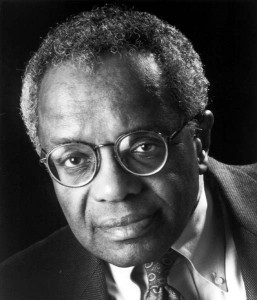

David Bradley

Bradley, 45, whose The Chaneysville Incident won the PEN/Faulkner award for best American novel of 1981, said in a recent interview that he had reluctantly concluded that race played a role in his termination. Bradley, an African American, said that he was not granted a hearing before he was fired, but that he knows of a white professor who was. He did not name the professor.

Bradley’s firing sent shock waves through Temple’s teaching ranks, where the action was perceived as a threat to tenure, the tradition of job security for professors.

“The university’s actions in this case constitute a clear violation of national standards for the protection of tenure and academic freedom,” the Faculty Senate Personnel Committee wrote in August, “and contradict the explicit provisions of Temple’s own contract and handbook.”

Bradley, a professor of English, began teaching at Temple 20 years ago and was a tenured faculty member for more than a decade. He was removed after a dispute with Dean Carolyn Adams over the terms of his contract, which called for him to teach four courses a year. That arrangement was negotiated in 1984 when Bradley, enjoying a growing reputation as a novelist, received an attractive offer from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Last year, Temple administrators ordered all faculty to add an extra course to their workloads to help ease a financial crunch. Bradley refused to teach the extra class, citing the 1984 agreement. He did conduct tutorials with two students in accordance with his usual teaching load.

In April, Adams notified him that his $80,000-a-year salary was being stopped and that his personnel records would show he had resigned his tenured position as of Dec. 31. Efforts to settle the dispute failed. — The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 15, 1996

Adrian Piper

Recently featured on this blog (in the A Beautiful (Black) Mind series) Dr. Piper was terminated from her tenured position at Wellesley College in 2008. This action came at the end of more than 10-year conflict between Piper and the institution over her contract , the conditions of her employment, her leaves of absence, and other issues. In 2002, Boston Globe reporter Vanessa Jones described the state of the professor’s tense relations with her employer at that time:

The school, [Piper] says, failed to help her juggle demanding careers in philosophy and art. Her hiring brought valuable publicity to the college, she says, but Wellesley refused her the sort of reduced course load and scheduling latitude universities often grant academic stars.

The stress, she asserts, forced her to take three medical leaves that have, together, kept her out of the classroom for three years. In the fascinating, chatty personal chronology she has posted on her Web site (www.adrianpiper.com) she describes herself collapsing from physical exhaustion at the end of fall and spring semesters, year after year. She writes about suffering from a rare spine condition that could only be improved by long sessions of yoga she no longer has the strength to continue.

…

Her most recent medical leave began in 2000. That same year, Piper filed a lawsuit accusing the college of discrimination and breach of contract. The complaint, part of the trove uploaded onto her Web site, details a raft of claims, but boils down to this: Wellesley hired Adrian Piper but wouldn’t let her be Adrian Piper.

The school hit back hard. In a motion to dismiss Piper’s claim filed last year, Wellesley said Piper had “exaggerated her medical condition, was malingering, and was attempting to renege on her teaching responsibilities.” It stopped paying Piper’s $98,000 salary last year; she’s now on unpaid leave. On the advice of college attorneys, Wellesley’s president, Diana Chapman Walsh and college dean Lee Cuba, declined interview requests.

Once again, I do not know the full details of any of these case, but I do believe that, taken together, they could constitute something of a trend. There seem to be common factors linking these conflicts together. For example, at least part of the conflict between each of these professors and his or her institution revolves around teaching responsibilities.

As the Boston Globe story on Piper points out, many high profile academics are given greatly reduced courseloads in order to accomodate what are often globe-spanning schedules of speaking engagements, exhibits, performances, residencies, and other appearances. Though these activities limit the scholar’s contact with students on his or her home campus, his/her high national and international profile benefits his/her institution through increased attention, enhanced reputation and a variety of other tangible and intangible rewards.

Something else that Bell, Cameron, and Piper have in common is the source of their notoriety. All are more widely known for the work they have done outside of their discipline than for publications within their academic field. Could it be that mainstream institutions have not quite developed a useful way of dealing with the African American polymath? Or could it be that the racialized focus of much of the Black polymath’s non-disciplinary work devalues that work in the eyes of their home institutions? Is it possible, for example, that the racialized subject matter of Derrick Bell’s brilliant speculative fiction diminished its significance in the eyes of his administrators?

And, how should an administration deal with faculty who protest against what they perceive as the racism of their institutions? What if that protest involves a withdrawl from teaching responsibilities? Do academic contracts include specific language on the maximum number of consecutive semesters a faculty member can be on leave? Should they?

In at least three of the four cases I mention in this post, the faculty member in question believed that he or she was wrongfully terminated. So, how can Black faculty protect their tenured positions? And how can institutions make clear their limits in terms of unpaid faculty leave and possible changes in courseload? Finally, to what degree does termination of a faculty member who is using unpaid leave as a form of protest constitute a violation of his or her right to freedom of speech?

Posted by Ajuan Mance