The history of people of African descent in the Americas is in many ways defined byo ur struggle to overcome the ways that both institutions and individuals have worked to limit our access to knowledge and experience. The great abolitionist and human rights activist Frederick Douglass wrote of his master’s mostly successful attempt to keep his slaves ignorant, by denying them even the most basic knowledge about their own world — their true age, their birthday, the names of their fathers, how to read and write, et cetera. For Douglass, this was the most powerful and effective tool of the slave owner, to prohibit Black peoples’ access to the very information that would allow them to

One of the strangest (and best) things about education is that the more you learn the more clearly you understand how little you actually know. If, as a college freshamn, I’d had even a vague sense of how much there was to learn about Black people in all fields of knowledge (art, literature, politics, history, education, science, mathematics), my education would have looked very different than it did. And my relationship to academia would have felt very different than it did, too. What a difference it would have made to me, as a student at a selective institution in New England, to know that African Americans had been attending and excelling at such institutions for at least 160 years before me.

The great debate of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was whether Black people’s education should be limited to vocational pursuits,or broadened to include the same in-depth study of history, literature, and science that characterized white post-secondary education. In many ways that battle is still being fought in the hearts and minds of Black students around the country. Our earliest Black predecessors in higher education, however, were unequivocal in their belief that the Black mind deserved and would benefit from the same opportunities to become enriched by the wide range of disciplines across the literature, sciences, and the arts that white students enjoyed. Today, we have the additional benefit of studying not only the products of European and Asian achievement in these fields, but also the products of Black scholarship and expertise.

I have compiled the following list of courses based on my believe that every Black student in the U.S. should, at the very least, acquire some sort of grounding in both the history of Black people and in the specific contributions of Black men and women to the humanities, sciences, and the arts. This list is designed to provide a framework for pursuing a greater understanding of the depth and breadth of Black history as well as the complexity and richness of Black culture(s), identit(ies), and intellectual work.

10 Courses Every Black College Student Should Take

1. African American History. The old adage says that history is told by the victors. If that is indeed the truth, then it should come as no surprise that Black history has captured the hearts, minds, and imaginations of people across the globe. After all, Black people have achieved a monumental victory in the U.S., first by emerging from slavery with pride and faith intact, later by defeating Jim Crow segregation and the racial terrorism or lynching, and most recently by alleviating the burden of racism enough that most of us are able to pursue own over versions of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. African American history is powerful, inspiring, and complex, and one course will not make you an expert; but it will open a door into a wonderful legacy whose heroes, heroines, and milestones will increase your sense of belonging in this nation as well as your sense of entitlement to the fulfillment of your dreams.

2. African American Literature. Since its inception, African American literature has functioned in dual capacities, as a rich and multi-genred art form and as a vehicle for communicating ideas about race and civil rights. Literature has been the primary tool used by Black people to inspire and transform hearts and minds, inside as well as outside the Black community. One of the best ways to understand the issues, questions, and ideas that have shaped and defined the lives of Black people in the U.S. is to read the stories that Black men and women have told. The novels, short stories, poems, plays, autobiographies, and essays that Black people have published over the last three centuries represent a consistent and evolving line of artistic inquiry into the meaning of race, color, humanity, freedom, and human rights.

3. Introduction to Women’s Studies. To study African American culture, literature, and history without taking into account the multiple ways that gender and sexuality have shaped and defined how Blackness is perceived and experienced is to fail to take into account a fundamental component in the marginalization and stereotyping of people of African descent. From the myth of the Jezebel to the stereotype of the hypermasculine Black male, the stereotypes erected to belittle and dehumanize us have been writ through with suggestions that our gender performance is wrong, degraded, and somehow deleterious to the morals of U.S. society. Let the intro-level women’s studies course be your initiation into those political, social, economic, and theoretical frameworks that are used to examine the impact of gender-based limitations, stereotypes, and expectations on all people’s efforts to achieve their life’s goals.

4. African or Afro-Caribbean History, or the History of Black People in Latin America. For most Black people who were kidnapped or sold into bondage, the middle passage did not end at what is now the United States. If you are part of the African diaspora and you live in the United States, then you should make it your business to a least begin to build your knowledge of the history of those Black people who live outside of this country. Take a course in the history of our ancestral home of sub-Saharan Africa, or else study the histories of those Black folks whose American odyssey took them to one of the other regions of the Americas.

5. The Bible as Literature. A redemptive and liberationist protestant Christianity is the religion that was passed down to us from our forbears. It is in many respects a beautiful and empowering legacy, but there are downsides to the fact that, as a people, our understanding of the Bible depends more heavily on the beliefs passed down from our parents and grandparents than on close reading and careful analysis. This is of particular concern given than the Bible might well be the the most complex and influential religious text ever produced. To study the Bible as literature is to engage the text as a critical thinker, under the tutelage of a scholar who will challenge all students in the course with questions, interpretations, historical frameworks that will challenge and refine (even as it adds nuance and depth) to your understanding of Biblical figures and events. It will also add breath, depth, and context to your knowledge of Christianity in a way that will enhance your understanding of its traditions and beliefs, regardless of your individual beliefs.

6-9. Four Semesters of a Language that is “Foreign” to You. There are many positive reasons for learning a language other than one(s) you were raised to speak, but I wish to address the specific ways that “foreign” language training can benefit the descendants of U.S. slaves. In addition to self-knowledge, slaveowners in the American south also sought to limit Black people’s interactions and abilities to communicate with each other. This was achieved by prohibiting slaves from visiting friends and family members who worked in other households and by prohibiting slaves from using non-verbal communication tools like drumming. Equally pernicious was the deliberatie effort by slaveowners to strip newly-arrived Africans of their languages. So effective was slaveowners’ use of violence, surveillance and threats, that within a surprisingly short amount of time people of African descent throughout the Americas had lost virtually all knowledge of their home languages. In the place of their ancestral tongues, eslaved Africans and their descendants adopted the colonizing languages of Portuguese, Spanish, English, and — to a more limited extent — French and Dutch. Today, these five languages aren the dominant languages of the African diaspora, in the Americas and — thanks to colonialism — in Africa, as well. To learn one or more of these languages (in addition to the one[s] that you were raised to speak) is to acquire a key tool for gaining richer and deeper sense of yourself, not solely within the context of our history as U.S. Blacks, but more broadly, within the context of the larger African diaspora.

10. A Year or Semester Abroad. Strictly speaking, a study abroad is not a course. Most do, in fact, include a program of several courses; but since most such programs are designed to cohere as an academic, linguistic, and cultural immersion experience, I am listing this as a course, for the purposes of this list. For the African American student, there are three main reasons to go on a year or semester abroad:

- To achieve fluency in a language (see above), a total immersion experience is very nearly a requirement.

- The experience of living abroad will transform your understanding of you home country in ways that few other things will. It is difficult to truly understand either the U.S. or your own Americanness in a global context until you have begun to travel the globe; and, depending on the region, you may well find that in many parts of the world your Americanness (the fact that you are from the U.S.) signifies much more strongly than your Blackness. It is a curious experience to have this form of identity privilege bestowed upon you, and I believe that every person of African descent should be able to feel this at least once in their lifetime. Few experiences can convey the gravity of the United States’ influence as an international power like the experience of the unearned privileged that is so often accorded to U.S. travelers in other regions of the world.

- There are many regions and nations in which your Americanness with be completely obscured by the fact that you are a person of African descent. In other places, the combination of your Americanness and your Blackness will mark you as a figure of great curiosity and interest. These experiences provide an understanding of the meaning and function of Blackness in a global context that is virtually impossible to achieve except in settings outside of the U.S.

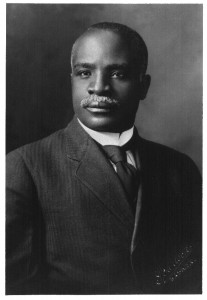

Posted by Ajuan Mance